Poland is the EU’s 6th largest economy by GDP with strong growth forecast for the years ahead. Here, we look at three things about Poland that marketers need to know – including overtaking the UK in household wealth, the rise of so-called ‘dark stores’, and the polarised currency debate.

Poland could overtake the UK in GDP per capita by 2030

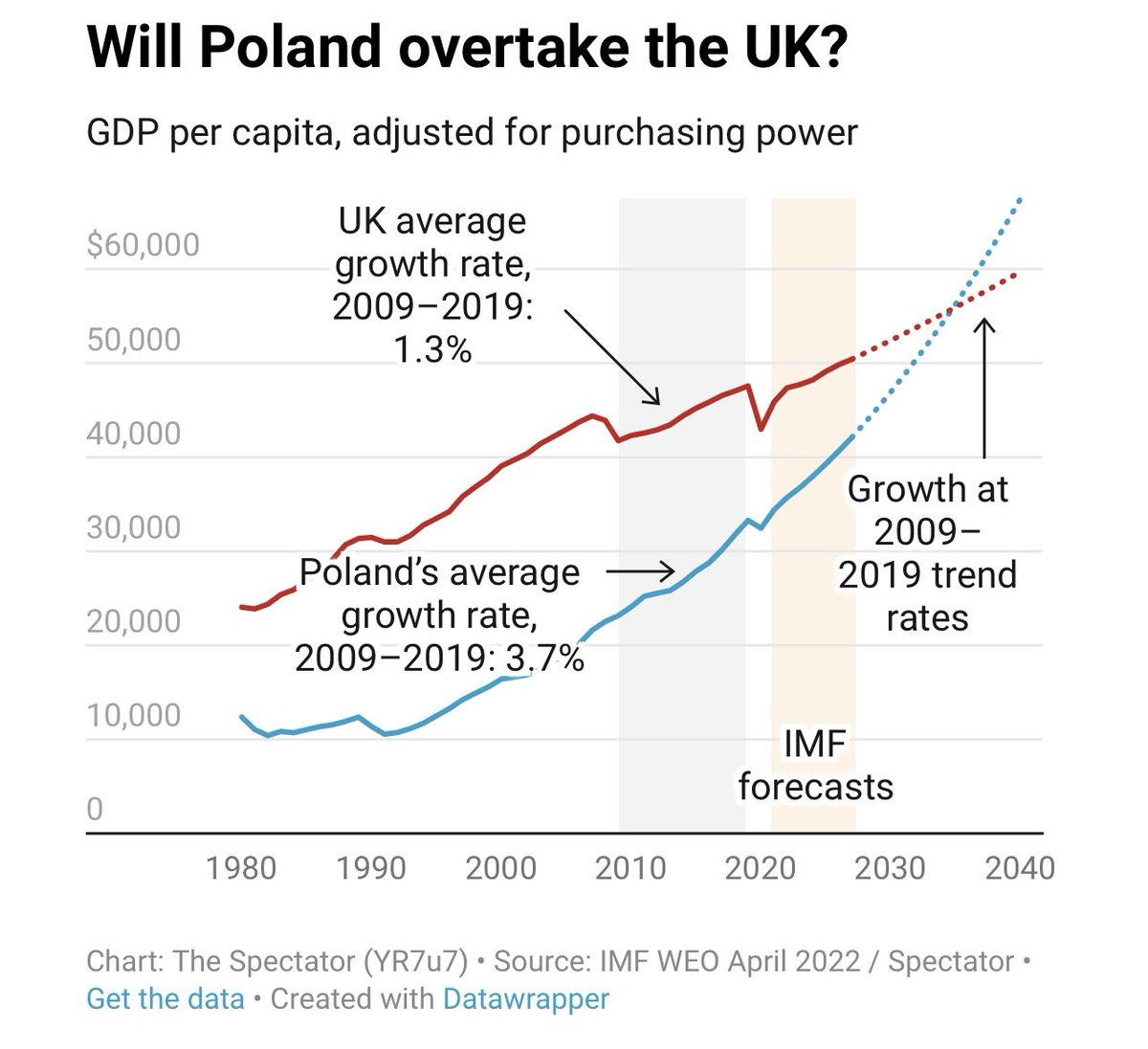

Recently, the Financial Times (paywall) suggested that, on present trends, the average Polish family will be wealthier than the average British family by 2030. The metric used was GDP per capita, adjusted for purchasing power. Here’s a chart from the Spectator which makes a similar point:

While politicians are keen on the headline GDP figure as the key metric for economic success, many argue that GDP per capita is a better reflection of a country’s wealth. (Britain is the 6th largest economy in the world by overall GDP, but only the 26th largest economy by GDP per capita.) Britain has had minimal economic growth for years whereas Poland has long enjoyed some of the highest economic growth rates in Europe. Today, cities like Warsaw, Poznan, Krakow, and Wroclaw are all wealthier – again, in terms of GDP per capita, adjusted for purchasing power – than Liverpool, Birmingham, Manchester, and Newcastle.

According to Eurostat data, Poland surpassed Portugal on GDP per capita in 2021 – making it the second ‘old’ EU state (after Greece in 2015) that Poland has overtaken. Poland was the only EU country not to experience recession between 2007 and 2009 during the financial crisis and was one of the strongest economic performers during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Such is the rate of Poland’s growth that the Polish government is campaigning to join the G20 – a forum for the world’s largest economies – and would like to replace Russia within the group. Poland’s GDP last year (over $655 billion according to IMF estimates) was significantly larger than those of South Africa ($415 billion) and Argentina ($455 billion), both of which attend the G20.

For British businesses looking for international expansion, Poland offers a growing market opportunity.

Polish cities are home to more and more ‘dark stores’

Poland has an expanding e-commerce market which in turn, has given rise to increasing numbers of ‘dark stores’. Dark stores are shops that have workers inside but don’t allow customers to enter, and whose storefronts are usually blacked out. Electric bikes parked outside hint at their purpose, which is to deliver goods to people’s homes within 15 minutes.

Customers place orders through an app and 10-20 minutes later (depending on the operator), their shopping arrives. This is less e-commerce and more q-commerce (with the ‘q’ standing for quick). Essentially, the dark stores are mini-warehouses or distribution centres.

Each dark shop is about 100-250 square metres in size. They are strategically located in city locations, allowing couriers to zip in and out. The locations are usually away from main streets, to be more cost-effective in terms of rent.

The first Polish quick e-commerce company to operate a network of dark stores was Lisek, which launched in 2018. (Lisek means ‘fox’ in Polish – the company logo is a fox carrying a shopping bag in its jaws.) Within a few months, the company covered a third of Warsaw and today, has expanded to eight Polish towns and cities. Its dark stores stock products similar to convenience stores – staples, ready meals, fruit and veg, alcohol and so on. The company only offers delivery through its mobile app and promises customers that they will receive their goods within 15 minutes.

There are about 10 operators in this space – Lisek but also players like Jokr, GetnowX, Bolt, Wolt, and others. In addition, traditional grocery stores have entered the market, such as Żabka with its Jush! Brand and Biedronka with Biek. So far, the market has focused on FMCG but there are rumours about potential entrants for building supplies and construction materials.

The mobile model has allowed Lisek and its competitors to operate on Sundays – when most regular shops must close – since Sunday trading laws exclude e-commerce.

Dark stores are not without their critics. They have caused concern among some urban activists, who worry that such outlets drain the life out of districts. The worry is that having ground-floor commercial premises functioning as warehouses with blackout windows – instead of conventional shops or restaurants – reduces city vibrancy.

Poland is unsure about joining the Euro

When Poland joined the EU in 2004, it accepted in its EU accession treaty that it will eventually join the Euro, though no timetable for doing so was agreed. Within Poland, the debate about whether to abandon the Zloty for the Euro continues.

Proponents argue that joining the Euro would bring Poland into the core group of EU countries and drive long term economic prosperity by further integrating Poland’s economy with western Europe.

However, joining the Euro would probably require a referendum since it would involve changing the Polish constitution which explicitly states that the Polish currency is the Zloty. Opinion polls consistently show that around two thirds of Poles are opposed to the idea of giving up their own currency.

Adam Glapiński, the head of Poland’s central bank, recently argued that Poland’s economic success had been achieved in part because the country has its own currency – which allows it to have its own monetary policy. Countries in the eurozone do not have their own monetary policy and rely on external decisions taken by the European Central Bank which are targeted not at their specific needs, but at the general need of the overall Eurozone.

During the pandemic, Poland’s central bank was able to move fast by relaxing its monetary policy and cutting interest rates. This translated into lower credit for consumers and helped the government to shield companies from the effects of the crisis. The drop in Polish GDP during the pandemic was three times smaller than the Eurozone average.

Poland at a glance

- Population of about 40 million people

- The leading player in Poland’s e-commerce market is Allegro, whose listing on the Warsaw Stock Exchange in 2020 was one of Europe’s biggest IPOs that year

- Founded in 1999, Allegro is the most popular online marketplace in Poland – ahead of both eBay and Amazon. Allegro is home to over 125,000 merchants – including some of the world’s biggest brands and many small and medium-sized Polish enterprises

- The most popular mobile payment in Poland is BLIK, mostly used for e-commerce transactions but more recently, for POS transactions too. BLIK is a joint venture between the largest Polish banks and Mastercard

- For Polish e-commerce shoppers shopping beyond Poland, the top markets are China, Germany and the UK

- Today, about 700,000 Poles live in the UK – down from a peak of over 1 million at the time of the Brexit referendum

. . .

Looking to grow your business internationally through digital marketing techniques? Oban can help. To find out how, please get in touch.

Oban International is the digital marketing agency specialising in international expansion.

Our LIME (Local In-Market Expert) Network provides up to date cultural input and insights from over 80 markets around the world, helping clients realise the best marketing opportunities and avoid the costliest mistakes.