Foot in mouth marketing and how to cure it

Recently, three large names have hit the news for all the wrong reasons. We explore the implications of cultural faux pas and how to avoid them.

Working from home is a commonly understood term to a UK audience, but around the world it’s known by other labels. For example, telecommuting, teleworking, homeworking, mobile work, remote work and flexible workplace are all used to mean broadly the same thing.

Before Covid-19, the International Labour Organisation estimates that 7.9% of the world’s workforce – around 260 million workers – worked from home on a permanent basis. In developed countries, working from home has typically been associated with knowledge-based industries – such as business, finance, professional and related services. In developing countries, that’s not always the case and working from home could include industrial outworkers (e.g. embroidery stitchers, beedi rollers) or artisans for example.

It is easier to work from home in developed economies. Many workers in developing markets are employed in occupations that can’t be done from home. For example, it is six times more common to be a street vendor in a low-income country than a high-income country, and 17 times more likely to be an agricultural labourer. In addition, the social, physical, and information technology infrastructure is often less adapted to home-based work in developing countries than in developed ones.

According to the ILO, around 30% of North American and Western European workers are in occupations that allow home-based work, compared to only 6% of sub-Saharan African and 8% of South Asian workers. Latin American and Eastern European workers fall somewhere in between at 23% and 18%, respectively.

This pattern may change: one consequence of the wider adoption of remote working might be the globalisation of white-collar jobs which have previously avoided being outsourced.

As well as the economic and occupational structures of countries, other factors determine a country’s rate of homeworking. These include:

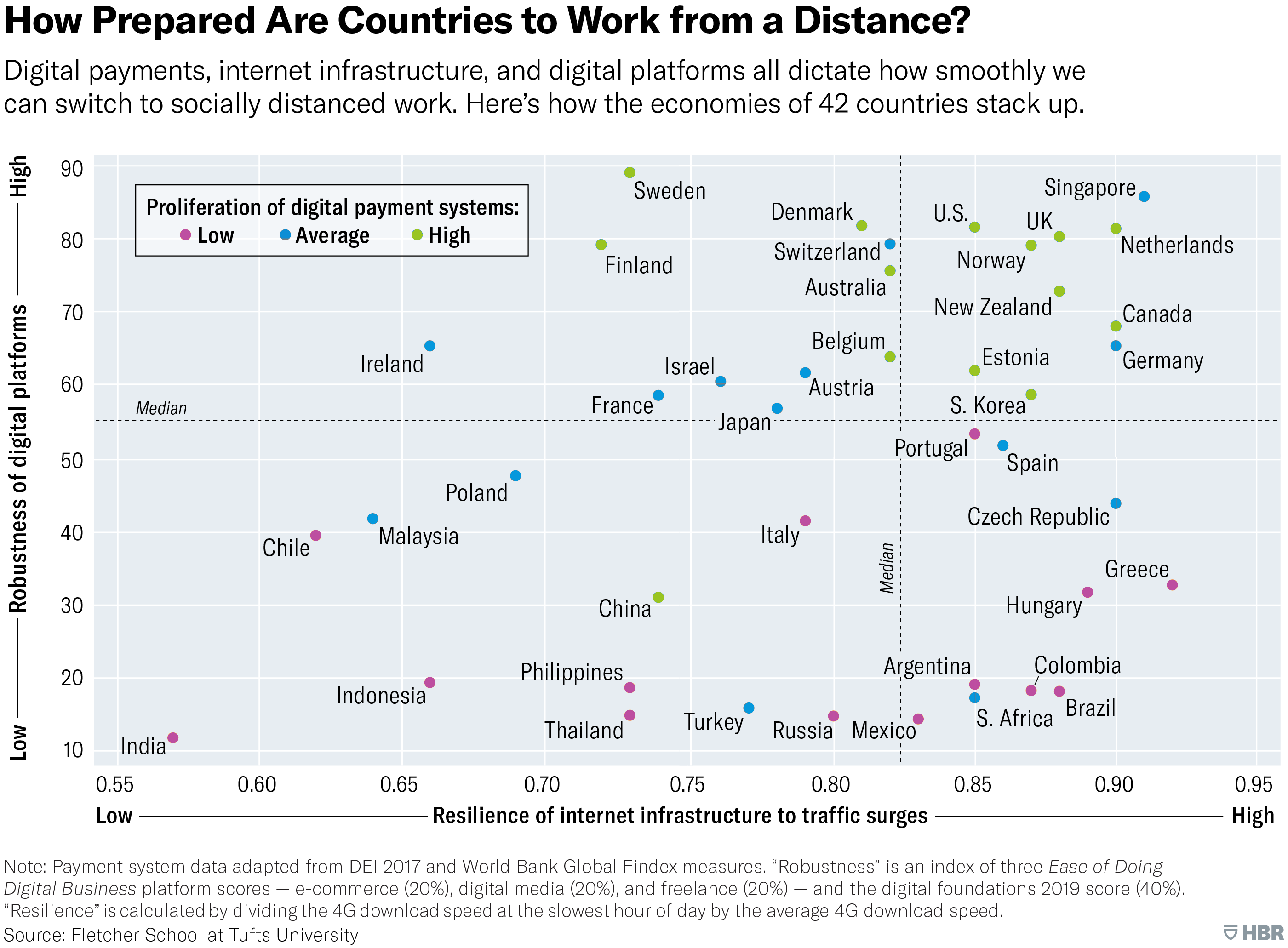

To assess how prepared countries are for remote working, Harvard Business Review plotted countries against two axes:

This was their conclusion:

(Source: Harvard Business Review)

Within countries, there are often significant regional and class variations in who can access homeworking. For example, the US is considered digitally advanced, with three-quarters of Americans having broadband access at home. But according to the Pew Center, racial minorities, older adults, rural residents and people with lower levels of education and income are less likely to have broadband service at home. In addition, 1 in 5 American adults access the internet only through their smartphone.

Whilst Scandinavia is well known for homeworking, perhaps less well known is Estonia. Estonia is the birthplace of Skype and the first country to allow citizens to vote online. The small Eastern European nation of just 1.3 million people has seen its population of remote workers grow to 12.5% from 3.8% of workers in the past 10 years, driven by the country’s continued investment in world-leading digital infrastructure and a rapidly expanding tech industry.

The country has actively sought to attract international remote workers. The country offers a pioneering e-residency programme, allowing businesses to be based in Estonia without a physical presence in the country. There are currently 69,000 digital residents of Estonia, located all over the world. E-residency has become popular with British entrepreneurs wanting to maintain a presence inside the EU, but it’s notable that the second largest group of foreign digital residents are Germans – already in the EU but attracted by Estonia’s digitised bureaucracy and lack of red tape.

Cultural attitudes to homeworking vary around the world. For example, Spain has traditionally lagged behind the UK and the US when it comes to homeworking. Antonio, one of Oban’s Spanish LIMEs (Local In-Market Experts), who has worked in various European countries, explains: “Spanish people often tend to be more sociable with work colleagues than British or Scandinavian workers. Sociability is something we value highly within the workplace.” In Japan, where long working hours and absolute company loyalty are admired, being a freelance homeworker rather than a full-time employee can be frowned upon.

Despite being well placed for remote working, Germans have been reticent in the past to embrace it. Germans place a lot of importance on in-person interaction between colleagues and can be more sceptical of flexible working policies.

Even in countries which are open to homeworking, it can vary by sector. The UK has been relatively open to working from home part-time, but in areas like London’s financial centre, before the crisis, a culture of working long hours in the office prevailed (“presenteeism”). In some countries, homeworking has been more prevalent amongst the private than public sectors, and amongst larger than smaller businesses.

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory sheds light on cultural attitudes to homeworking. One of the axes in Hofstede’s theory is individualism versus collectivism. The more highly a country scores on the individualism index, the more likely homeworking is to be valued. That’s partly because power and status are highly valued in individualistic societies. Traditionally, homeworking has been reserved for senior individuals which means there is some status attached to it. Individual societies prize achievement, so the opportunities for self-determination and proactive initiative in homeworking are likely to be respected. In collective societies, managers may fear that homeworking will undermine the organisational or collegiate sense of solidarity or collective responsibility.

To find out how an international growth agency like Oban can help you navigate the post-Covid landscape, please get in touch.

This is the third part in Oban’s three-part blog series on working from home. Click here to read the first part which explores how large-scale homeworking will affect where people choose to live and work. Click here to read the second part, which explores the knock-on effect on other categories.

Sarah Jennings | CEO

Oban International is the digital marketing agency specialising in international expansion. Our LIME (Local In-Market Expert) Network provides up to date cultural input and insights from over 80 markets around the world, helping clients realise the best marketing opportunities and avoid the costliest mistakes.